Dieser Text ist zur Zeit nur auf Englisch verfügbar...

Massive scleractinian corals growing in our tropical oceans are ideal environmental and climate archives because of their ability to record changes in ocean-atmosphere interactions in its calcium carbonate skeletons. The skeletons of these corals are continuously deposited for up to hundreds of years at a single location and Dr. Wu’s research is focused on using the geochemical signatures locked inside these skeletal materials to understand climate change of the past two thousand years.

Dr. Wu and his research team have investigated the behavior of tropical climate in the Common Era over multiple timescales from the sub-seasonal to the decadal-interdecadal and centennial using corals. His research group’s use of paleoclimate and paleoceanographic proxies (physical characteristics of the past represented as direct measurements) such as stable isotopes (e.g. δ13C, δ18O, δ11B) and trace elements (e.g. Sr, Li, Mg) are common in marine biogeochemistry and enables the reconstruction of past climate from coral skeletons. Coral core samples as recorders of the environment can be of modern age existing in the anthropogenic era or fossilized specimens from the deeper geological past.

Many of the research questions central to Dr. Wu's investigations involve the large-scale changes of tropical ocean sea surface temperature (SST), salinity (SSS), evaporation-precipitation, seawater pH and carbonate chemistry, and ocean circulations. The ocean and climate change interpretations are only as accurate as the proxy and Dr. Wu also aims to improve the reproducibility and reliability of proxies’ analyses and reconstructions. Finally, understanding the changes and interactions of the ocean-atmosphere and climate systems in the past will be critical to predicting climate under future climate change scenarios.

Jump to the following Topics:

- OASIS Project Webpage

- News of the Working Group

- Ocean Acidification

- Coral-based climate reconstructions

- Climate and the collapse of the Maya Civilization

- Study sites of the Coral Climatology Research Group

- Research approaches and methods

Current Research Topics

Make Our Planet Great Again!

OASIS

Ocean Acidification

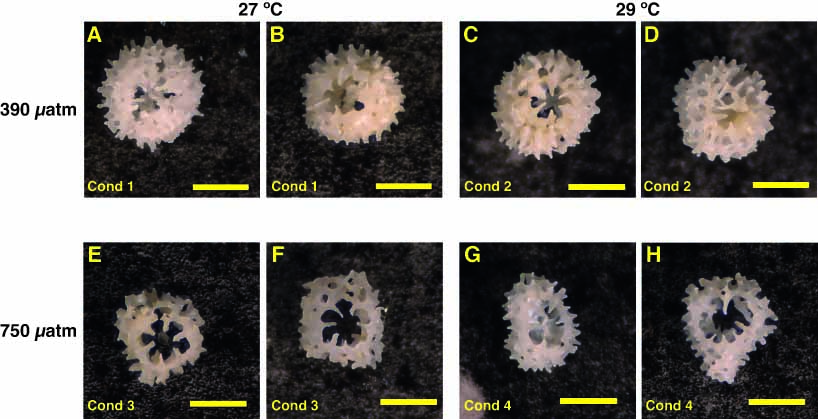

The pumping of CO2 into our Earth's atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution not only warms our planet due to the Greenhouse Effect but the absorption of anthropogenic atmospheric CO2 by our oceans is also severely impacting calcifying animals living in our tropical oceans.

Here's an example of ocean acidification impact with individual primary polyps of Acropora millepora juvenile corals (single corallite) cultured in four experimental conditions. (A, B): Condition 1 (control; 27ºC with 390 ppm pCO2) revealing normal skeletal materials. (C, D): Condition 2 (warming with no ocean acidification; 29ºC with 390 ppm pCO2) revealing more translucent skeletal characteristics relative to condition 1. (E, F): Condition 3 (no warming with ocean acidification; 27ºC with 750 ppm pCO2) revealing decreased bulk volume and skeletal materials. (G, H): Condition 4 (warming with ocean acidification; 29ºC with 750 ppm pCO2) revealing more asymmetrical, translucent, and brittle skeletal materials. All scale bars are 500 µm. (Wu et al. 2017).

Coral-based climate reconstructions

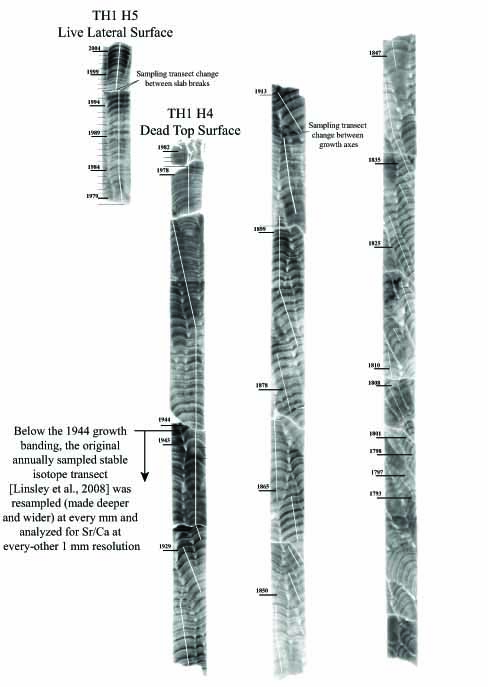

Using corals as archives to document climate change: X-radiograph of coral growth revealing the density layers deposited every year similar to tree rings or ice cores.

X-ray collage of the Kingdom of Tonga microatoll Porites sp. colony with cores TH1-H4 (dead top surface) and TH1-H5 (live lateral surface). The micro-sampling paths on the coral skeletons are the transects followed to retrieve the skeletal powder for geochemical analyses. (Wu et al. 2013).

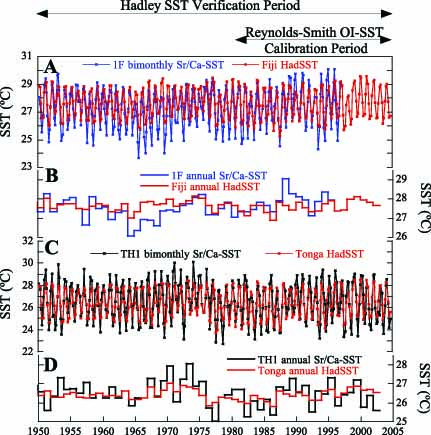

Reconstructing sub-seasonal climate and surface ocean conditions or variations (e.g. sea surface temperature, salinity) in the tropical Indo-Pacific using coral geochemical records, also known as proxy records (e.g. stable isotopes, trace elements).

Coral-based Sea Surface Temperature (SST) reconstruction. Bimonthly-resolved Porites sp. coral Sr/Ca records from Fiji and Tonga revealing annual seasonal cycles related to SST compared to instrumental SST records from the UK Met Office Hadley Centre observations dataset (HadSST). (Wu et al. 2013).

We use the proxy records from coral skeletal materials to interpret long-term deviations or changes in the Pacific Ocean such as the significant spatial and temporal evolution of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) seen here based on SST variations.

Current observed Sea Surface Temperature (SST; ºC) and Sea Surface Temperature Anomalies (SSTA; ºC) for the forcast of El Niño-Southern Oscillation Events (El Niño or La Niña). Weekly averaged SST and SSTA for the previous 12 weeks. Anomalies are calculated as departure from the adjusted climatology. NOAA Climate Prediction Center (Reynolds and Smith, 1995).

Collapse of the Classical Maya Civilization

We use precisely dated fossil coral skeleton records to interpret the changes in climate (e.g. sea surface temperature, salinity, precipitation) on the Yucatán Peninsula, which led to the prolonged droughts that possibly brought on the demise of the Maya Civilization during the Termical Classic Period (Year 750–1050 Common Era).

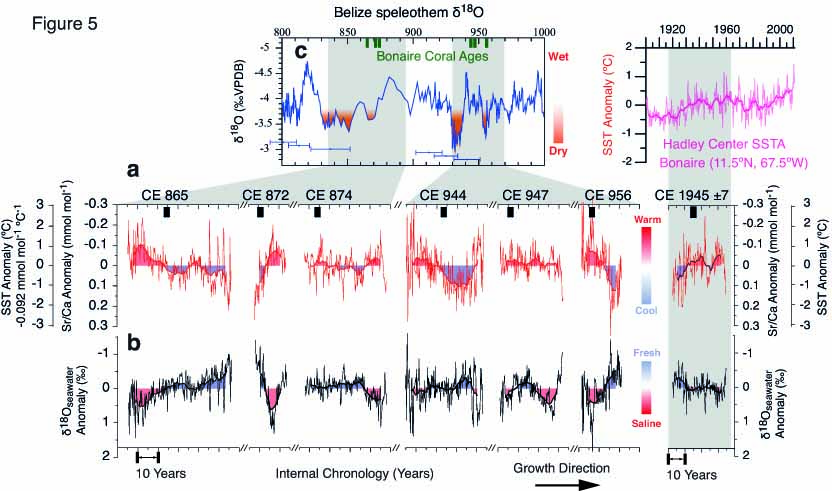

Comparison of Bonaire coral-derived Sr/Ca-SST and reconstructed δ18O of seawater (δ18Osw) records to the Yok Balum Cave, Belize speleothem record. Six Bonaire fossil corals that indicate large perturbations in SST and SSS are shown (a) with the most well-dated Yok Balum Cave speleothem δ18O record (precipitation) throughout the entire Terminal Classic Period (TCP; ~CE 750–1050). The horizontal error bars indicate the dating uncertainties of this summer precipitation record. The precision coral 230Th/U-age is shown (black squares) along with (b) close-up overlapping time windows of the speleothem δ18O record. (c) The Sr/Ca-derived SST anomaly and (d) reconstructed δ18Osw anomaly (proxy of SSS) records during the TCP. The fossil coral records depict warm/saltier (orange) and cool/fresher (blue) conditions similar to the drought conditions (orange shadings) of the speleothem record. (Wu et al. 2017).

Study sites of the Coral Climatology Research Group

- Previous and Current locations: Palau, Clipperton Atoll, Fiji, Tonga, Rarotonga, Bonaire, Indonesia, China, New Caledonia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Fanning Island, Wallis and Futuna, Tuvalu, Tokelau, Rotuma.

- Coming Soon: Caribbean Sea.

Research Approaches and Methods

When not out in the field observing and collecting coral samples for science, our research team spends a lot of time in the chemistry laboratory preparing and analyzing the tropical coral samples for stable isotopes and trace elements as climate and environmental proxies.

We utilize the high precision Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS; Thermo Fischer Scientific MAT 253) for the analysis of the proxies, δ13C and δ18O.

For trace elements analyses, we utilize the Inductively Coupled Plasma – Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS; Analytik Jena Q-ICP-MS) and Optical Emissions Spectrometer (ICP-OES; Spectro Cirro ICP-OES) to understand the changes of Sr/Ca, Li/Mg, B/Ca, U/Ca, Ba/Ca, and other ratios.

For coral skeletal δ11B signature analysis, we require the Multi-Collector ICP-MS (Thermo Fischer Scientific Neptune Plus MC-ICP-MS).

The Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) is also often utilized to examine the fine and detailed skeletal microstructures of the coral samples for chemical and biological alterations and preservation state.