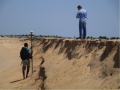

Phillip surveying the high-water line with the high-resolution GPS | Photo: TM

Coastal processes are controlled by natural and artificial influences acting over variable time scales, from daily to centennial or even millennial. The coastline of Ghana has experienced severe shoreline erosion during the 20th century. The reasons for this recession are still not clear. It may be partly related to the building of the Akosombo dam in the Volta river in the 1960´s, which literally starved the shoreline of sediments. However, insights from anecdotal knowledge indicate that shoreline erosion was a critical issue even before the building of the dam. In the beginning of the 21st century, extensive stretches of the shoreline east of the Volta estuary were stabilized by groynes and bank revertments. Additionally, land was reclaimed by beach nourishment. Since then, the situation apparently improved and local fishermen were able to land their catch again. Within the frame of the project “New Regional Formations” funded by the VW Stiftung, four researchers (Elisa Casella, Alessio Rovere, Benjamin Lassalle and Thomas Mann) from ZMT and MARUM were heading off to Ghana in order to monitor and sample the coastline around Keta in collaboration with colleagues of the University of Ghana. They surveyed beach topography with high-resolution GPS, unmanned remotely controlled aerial vehicles (UAVs) and basic sediment sampling techniques. The results will be implemented in a long-term shoreline change analysis that will help assessing coastal risks and vulnerability and how these environmental changes influence the livelihood and migrational pathways of the local people.

10. – 18.5.15

Every field mission is carefully planned before leaving. The plan was to collect sediment samples from the shoreline, to be then analyzed in Germany with respect to their relative heavy mineral distributions. Another part of the plan was to make, in correspondence to every sample, a GPS cross-profile of the beach and, in suitable areas, fly our unmanned aerial vehicle to gather zenital pictures of the shoreline and reconstruct, through a method called structure from motion, the 3D-model of the beach. Some of the roads in the Keta area run perpendicular to the sea, so originally we thought to sample and do our transects in correspondence of such roads.

The most challenging moment of any fieldwork is when you suddenly realize either that the plan you made sitting in the office would not work, or, when things go well, that you can do better than you expected. That is the moment when all bets are off, and you have to be flexible. A bit afraid of the heat in Ghana (the temperature reaches 34 degrees and humidity is 83%), we did not plan to acquire data on the position of the shoreline (or, better, of the high tide mark).

This would have meant walking for around 20 kilometers on the beach carrying the GPS. But once there, we thought that it was actually possible to do it, waking up early in the morning and making shifts in carrying the GPS. We divided in teams of three, and we divided the shoreline in stretches of 500m – 1km each. We carried the GPS to the next beach access by road, where the other fresh team would take a sediment sample and start their stretch of walk. We did it for 4 long days.

In the middle of all this, there was Africa, as beautiful and though as it could be. In our hot and humid walks, we encountered fishermen singing to give themselves the right cadence while pulling nets out of the water. Kids running towards us, singing in Ghanian ‘White man, black beard’ and laughing with pure joy, trying to just touch us. Elder people amused seeing Benni taking sediment samples in jeans and t-shirt, not caring about the waves hitting him. Women greeting us with a simple ‘welcome!’. and people asking if we were from the government planning some new development in the area.

Once samples were in the bag, and data safely stored in our GPS, it was time to get airborne. Elisa and Alessio had agreed that during this trip they would train Philip and Trinity to do surveys with UAV, so they will be able to come back every two months for a year with a similar UAV owned by the University of Ghana. This will be essential to assess short-term shoreline variations and improve models of coastal erosion. We planned a total of 10 flights in different hotspots of erosion along the beach, and our two remote pilots had their hands full trying to perform the flight, teach their ‘magic’ to our colleagues and deal with the multitude of Ghanian children that would literally submerge us after each landing.

Flying an unmanned aerial vehicle (we call it ‘drone’, hoping that the mind of the reader will not go to war scenarios) is not an easy task. It requires a pilot, who has the commands in his hands, and a co-pilot, who checks the sky for obstacles and monitors the flight while in GPS mode (a sort of auto pilot, which will perform a pre-programmed route). Doing it is not easy, but teaching it to someone who never did, and in few days, it is even harder. This is why we all felt a sense of accomplishment when both Trinity and Philip, after almost 4 days of intensive training, performed a perfect flight together and landed safely.

The last two days saw us coming back to Accra (no traffic jam this time) and have a final meeting with our Ghanian colleagues. We were shown the campus, we exchanged data, and we walked out of the meeting room with the promise that an active and strong collaboration is born, and this is not the last time we worked in Ghana.

7. – 9.5.15

Our flight to Keta was smooth. We left a chilly but sunny Bremen day to arrive in the Ghanian Capital, Accra, late in the evening. As often happens when arriving in tropical countries, the heat and humidity caught us off guard, and taught us the oldest of the lessons: when you complain about the rigid Northern German climate, be careful what you wish for.

The first step when travelling for research is to ‘check in’ at the Embassy of your country. Therefore, in the early morning of May 8th, we met the permanent representative in the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany in Accra. We described him the project and its aims, and in return he shared some of his knowledge on Ghana, offering help and support if needed.

The best part of working in foreign countries are the colleagues you get in touch with. And the best part of fieldwork is that, after lots of email exchanges you get to meet them and start working together (and, why not, having fun in the process). This is why, straight after visiting the Embassy, we went to the University of Ghana, where we met the two people that literally made our trip possible: Dr. Kwasi Appeaning-Addo and Dr. George Wiafe. Together with them, we were greeted by Mr. Philip-Neri Jayson-Quashigah (PhD student) and Mr. Trinity Mensah-Senoo (research assistant), two students who joined us in the field.

After setting up our equipment in the evening of the 8th, we were ready to ‘rock’n roll’ early morning the 9th, leaving from Acrra to Keta. The plan was to get to Keta early in the afternoon the 9th to relax and enjoy before starting to work the 10th. In theory, Accra-Keta is a 2.5 hrs drive along a pretty good highway. In practice, we got stuck in what we thought to be the biggest traffic jam in Africa ever. Our local colleagues, instead, informed us that the jam we were in is just normal Friday traffic in the outskirts of Accra. We went to sleep in Keta knowing that the following days would be hard.

Thomas Mann, Benjamin Lassalle, WG Geoecology and Carbonate Sedimentology / Alessio Rovere, Elisa Casella, WG Sea Level and Coastal Changes